De-Escalation: Linking Internal and External Communication

De-escalation practices have undergone significant evolution, characterized by a more rapid cognitive processing and an empathetic communication framework. This evolution can be traced back to historical incidents, notably the case of Eula Mae Love, a 39-year-old African American mother who was fatally shot by the Los Angeles Police Department on January 3, 1979. Had contemporary de-escalation strategies been employed during Mrs. Love’s incident, it is conceivable that the outcome could have diverged significantly. Despite advancements in de-escalation tactics over time, there remains a need for further education and skills enhancement in this domain.

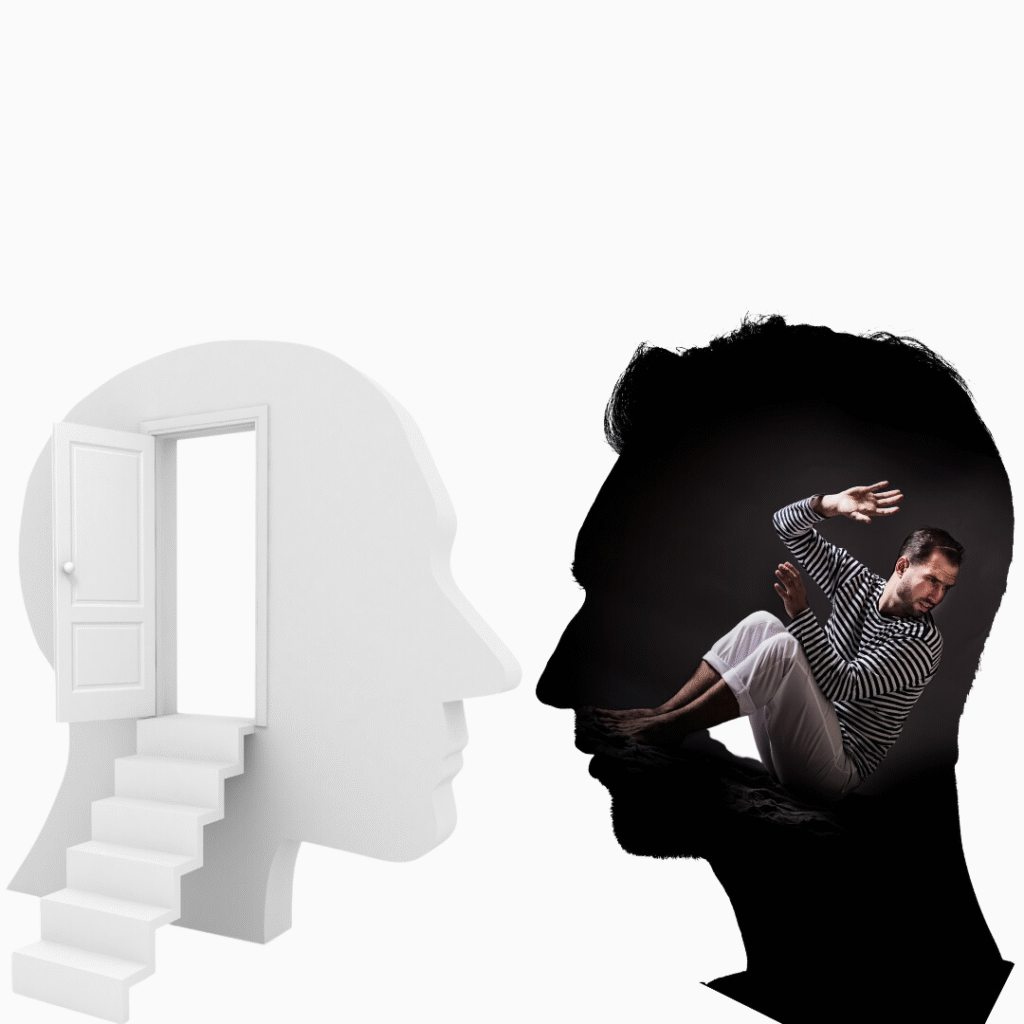

A critical component of effective de-escalation efforts is the interplay of internal and external communication. Unfortunately, these dynamics are often underrepresented in law enforcement training curricula. To clarify, internal communication encompasses the private thoughts and cognitive processes occurring within an individual, while external communication involves the expression of those thoughts verbally or in writing. In confrontational scenarios, what might appear as a singular dialogue is actually multifaceted; two individuals engaged in conversation are simultaneously contributing four streams of communication—two external (the spoken words of each participant) and two internal (the unvoiced thoughts and interpretations inherent to each individual).

During the de-escalation process, officers must navigate the verbal exchanges while simultaneously processing their own internal dialogue. This duality also extends to the subjects or suspects involved in the encounter. Internal communication can lead individuals to tailor their verbal expressions based on contextual factors, emotional states, and the nature of interpersonal dynamics. Overwhelming internal dialogue can impede comprehension of the other party’s words, potentially escalating frustration and misunderstanding. Behavioral indicators of individuals grappling with internal monologues may include blank stares or delayed responses.

Conversely, external communication may not accurately reflect an individual’s internal state. Environmental influences, emotional responses, and the rapport established with interlocutors can significantly impact how messages are conveyed. An individual may exhibit heightened aggressiveness in their verbal communication when their external expressions conflict with their internal thoughts. Misinterpreting this behavior can lead to detrimental responses from officers, diverting the interaction away from a constructive exchange that encourages a shift from internal to external communication, creating clarity and understanding.

In daily interactions, everyone engages in both internal and external communication. During de-escalation, officers must strive to comprehend not just the overt messages being articulated but also to discern the internal motivations that inform those verbal expressions. Employing this nuanced approach enables officers to achieve greater understanding and empathy toward the individuals involved, preventing assumptions driven by initial behavioral responses. It is essential to recognize that police officers often juggle multiple professional roles under time constraints while navigating numerous safety considerations. For this process to be truly effective in de-escalation, it’s important for officers to actively practice and embrace the use of open-ended questions. This approach not only enhances communication but also encourages a collaborative environment, paving the way for more constructive interactions.

What are your thoughts on the role of internal and external communication in de-escalation? We would appreciate your insights.